The sign warns people to stick to the marked path. But a man sawing timber for a new foot bridge tells us to be extra careful of the red mud that has washed over the path.

Our guide, Carleigh Toupin, tells us to tread where she treads. The logs placed across the mud are slippery; the mud itself can swallow your boots, your whole leg, in an instant. It's like quicksand.

We're in Huonbrook, one of the many valleys above Mullumbimby shattered by the February 28 rain bomb and hit again a month later.

We have a brief window of opportunity to get in and out. Work to stabilise the road up to the valley means it's only open to residents and visitors for a few hours a day.

Beyond the sealed section, landslides have taken out the road and the power and the telephone line used by about 100 Huonbrook residents. From here, it's a gruelling walk across the face of the landslide and along a path cut by the community, with help from a Fijian army detachment.

A cache of supplies is set up under a tarpaulin. Residents navigate the track to pick up what they need and hump it back to their homes.

As we make our way warily along the track, Caileigh keeps a raptor's eye on the rain. It's light and gentle now - "nuisance rain", she calls it - but should it get heavier, it could become dangerous.

If you hear thunder, run

We meet Jaye Dunlop, a 38-year-old builder, who lives in the valley. He tells us his neighbours are all elderly. "The next youngest is in their late 60s," he says.

"They're OK with a hand down but that's why we're building pallet stairs over the slide and trying to make it more accessible. But the weather's challenging."

A geomorphologist has been out to investigate the ruined road and the landslide, Jaye says. To fix it is an engineering challenge most likely beyond the ability of the local council.

He points out the remains of a track and footbridge washed away in the second flood in March. On one side of the creek that runs alongside what was the road, a scar of mud, rock and fallen trees extends up the hill. There's water flowing down the middle, a stream fed by the seemingly endless rain.

"The geomorphologist said when you get to that point, just jog," Jaye says. And, he adds, if you hear something which sounds like thunder, run. It's not thunder; it's the earth moving again.

In this part of the world, with its steep sided valleys, intricate creek systems, forested hills and heavy rainfall - all of which make it achingly beautiful - the earth does indeed move. Jaye says back in the 1950s, the road into Huonbrook used to be on the other side of the creek. And after the February deluge, he says, the creek is now wide enough to handle a lot more water.

Communities are doing it for themselves

We're accompanying Caileigh as she checks on the welfare of some of the more isolated residents. It's part of her role at the community-led recovery centre based at the CWA Hall in Mullumbimby.

It's an impressive outfit, seemingly run along military lines, with heads of departments, operations managers, specialists and task lists. The atmosphere in the CWA Hall is very much like a command centre.

Caileigh's role is to co-ordinate relief to the hinterland communities isolated by landslides.

"We've got a ground crew which amazing. They're experienced hikers, experienced ropers and they're the ones that have been going up and doing a lot of the hard yards of getting into these communities.

"The ropes and the footbridges and all these different tasks have been to give the communities that are still there, that are are still unable to get to town or get to any of the essential services, a way to access them."

Just as the community led the rescue response in Lismore when the flood overwhelmed the emergency service agencies whose job it was, the community is leading the relief response in the hinterland.

"There's a lot of shocking truths in all of this," says Caileigh.

"It can be very dangerous, it is a bigger job than you would expect the community to have to be doing. But that's who's here and that's who's doing it, you can't just put your hands up and say it's someone else's problem."

Ella Rose Goninan, who heads the operation, says it is not getting the support it needs from all levels of government.

"I wouldn't say we're not getting any but we're not getting the suppor0t that's required for those areas.

"We are mobilising as much community support as we can and the challenge with that is, I guess, to keep it coming. We need a lot to help these areas get sorted out - everything from essential supplies through to road works and engineering," she says.

First came the fire, then the flood

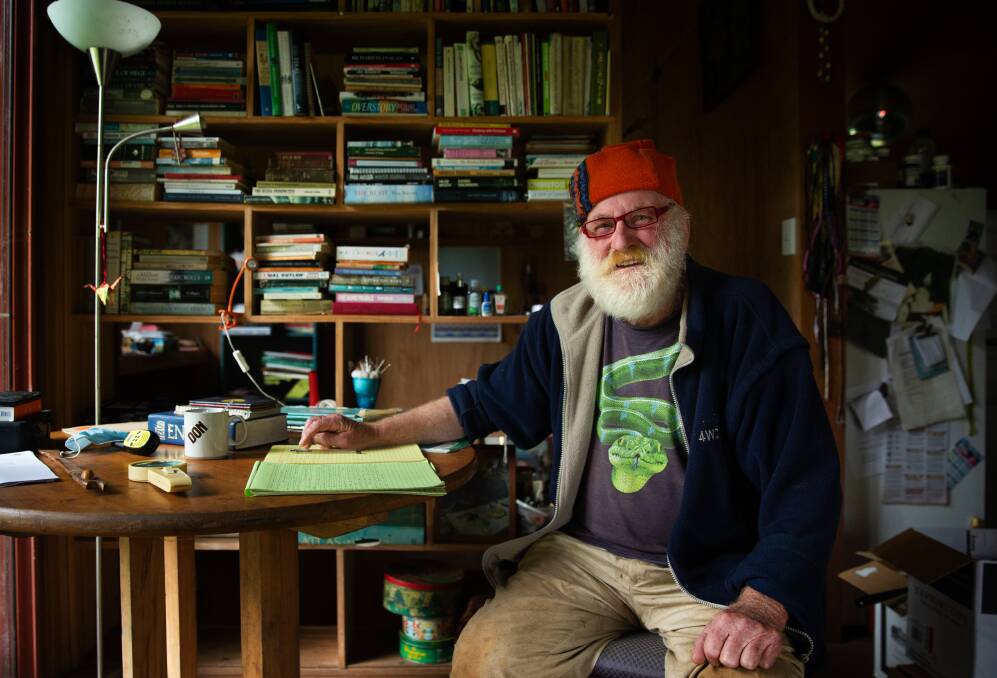

Deep in the Huonbrook Valley, Don Drinkwater has stared down two climate catastrophes in as many years. Once a cattle property, his land is now reverting to rainforest, thanks to his planting efforts over the 45 years he's owned the place.

But it's a precarious paradise he's fashioned.

First came the fires in late 2019, then the flood in 2022. But he's not planning on going anyway.

"Oh, I'll die here," the 74-year-old says matter-of-factly.

"When you live here you get over your fear quite quickly because you've got to deal with it."

The abiding memory of the fire, which saw the rainforest burn for the first time in living memory, was the wind.

"There were ferocious winds, winds like I had never seen before. They would come through for probably five minutes in all different directions and then they'd be over, they'd be gone."

The winds brought embers that would ignite spot fires in his vegetable garden. Trees had fallen over the road out so he couldn't evacuate.

When the flood came in February, it was the noise Don remembers most vividly.

"You didn't sleep. Once the rocks started to move down the creek and the trees started to fall, the roar was extraordinary. I've never heard a roar like that in my life and I've lived in a lot of places."

Many of those rocks which were washed down the creek were the size of cars, such was the force of the water.

"We've never seen anything like it before. In 36 hours, we got a metre of rain.

"When that happened you just put the pillow over your head. It was dark, the power was gone and the telephone was gone. You just had to sit tight."

And sit tight for the rest of his days is what he intends to do.He still has enough food from his garden and is grateful for the help he's received from Caileigh and her team in Mullumbimby.

"It's been phenomenal really. They ask every time if there's anything I need and that's greatly appreciated, just their thought."

With the still power out, and reluctant to use the generator he's been lent - "It's too noisy" - he's happy, catching up on reading and writing his memoirs.

His only regret is that no one in leadership has properly addressed the climate crisis, which has put his existence at risk.

"The writing has been on the wall for a long time and we haven't heeded it. We don't like to listen to what we don't want to hear. I think that's the saddest thing. That's my grief really."

Resilience is being agile and connected

In another valley on the other side of Mt Jerusalem, Mel Blor greets two Rotary members who have driven from Nerang in Queensland to Uki to deliver a trailer load of steel star pickets to help landowners who have lost fences.

Mel found herself in what she calls a "Mama Bear" role after the flood hit the town and surrounding valleys.

"We had twin floods in the first flood. The water came up and then went down again. Then we had another weather front come in. At that point the ground was as wet as it could be. Every drop that fell in that second front ran across the surface of the ground," she says.

The river rose higher than it's ever done before, low lying areas were inundated, along with homes which sat on them. But it was in the upper valleys - on higher ground - that the deluge did its most widespread damage.

Landslides cut roads and driveways, the flood took out power and communications as well as the town's water treatment plant. Up in the hills, neighbours immediately began to check on each other. Just as it was in Lismore, the community was the first responder.

The Uki School of Arts become a hub, for relief supplies and, just as important, information.

"We would stop people who were driving past and go, 'Can you get through that road this way?' We put bits of butcher's paper out the front and started writing information down and it progressed from there," Mel says.

"I personally didn't come into the town for a few days because I was digging my neighbours out and creating avenues for them to be able to walk down to a more centralised spot without risking their lives."

She says the key to community resilience is to be connected and light on your feet.

"So you can mobilise and move and adjust to what the new situation is, whether that's an acute moment like a flood or a fire, or a more chronic moment."

Resilient communities. she says, are strong because they're connected, not only with the people within them but the landscape around them. There are, of course, technical things that can strengthen that connection. Mel is working with another community, Main Arm, to have a UHF radio tower installed on the hill between them so they can communicate with each other should another emergency knock out power and communications.

Disaster experience helps remote community

In Main Arm, at Kohinur Hall, we meet Simon, who's been running the relief centre there since the flood struck. It's not his real name - his work in disaster and conflict zones around the world demands anonymity, he says.

*The devastation wrought by the flood is piled all around the hall - wrecked cars, fallen trees, huge gashes in the landscape left when the Brunswick River exploded in an unstoppable torrent.

"In the immediate aftermath we didn't know where everyone was. We didn't know how many landslides we had. We had quite a few houses completely destroyed, some with mud coming into the bathroom, houses pushed off their footings and a lot of people trapped in or out," he says.

It was only because neighbours were checking on each other that two who were trapped in the rubble of their home for 30 hours were found. Communications were so patchy, one person had to climb to the summit of Mt Jerusalem to get enough phone signal to alert authorities to the effort to free the trapped people, which involved six hours of digging.

"If we had proper comms we could have had half the community out there supporting them."

His community tried to get funding for a UHF network and repeater station after the 2019 fires. The flood has added urgency to that need. There are plans to have the donated generators and other equipment stowed in a shipping container for the next emergency. Community members are also being encouraged to undertake SES training in how to respond to such disasters.

Where the muddy hell are you?

When Scott Morrison visited Cobargo on the NSW Far South Coast after the Black Summer fire decimated the town on the last day of 2019, his attempts to force handshakes on exhausted firefighters became infamous. So infamous, they're being used in Labor Party attack ads.

He didn't make the same mistake when he visited Lismore after the floods in March. He made a different mistake, avoiding media scrutiny of the visit, apart from an angry press conference at which he conceded Australia was becoming a harder place in which to live.

It would have instructive for him to spend time at the Koori Kitchen set up the car park opposite the offices of the Koori Mail, to get a handle on the importance of community in the face of disaster.

When flood damage forced the suspension of publication of Australia's longest running Indigenous newspaper, the Koori Mail's staff quickly pivoted to setting up relief for the beleaguered city.

"We've turned ourselves into a community run grassroots organisation here, providing flood relief support for victims of the Lismore floods,' says Koori Mail general manager Naomi Moran.

"What we chose to do was to make sure that we were in a position to look after the community with any kind of relief support following the flood."

There's a food bank, where people can grab essential supplies, a medical service offering GP and registered nurse consultations as well as mental health referrals.

"We have a kitchen across the road providing hot meals, serving up to 700 or 1000 hot meals every day to those that are need but also supporting our volunteers and workers that are on the ground."

Community should come first

Retired ACT Emergency Services Chief Peter Dunn says the community needs to be at the top of the decision making process after any disaster.

In 2019, he found himself at the pointy end when the Black Summer swept the NSW South Coast, destroying dozens of homes in Conjola Park and cutting off neighbouring Lake Conjola, where he and his wife were living at the time.

He helped lead the town's relief and recovery efforts. He says the pyramid of decision-making needs to be tipped on its head.

"Sitting at the top is the prime minister of the country. Sitting down at the bottom are the people. That's the hierarchy of decision-making," he says.

"In a disaster, particularly with the turbocharged, extreme weather events we have at the moment, you have to tip that pyramid upside down. You have to put the community at the top and everybody works to support those communities because they are hurting so much."

And, of course, it is those communities that continue to do the heavy lifting long after the disaster has faded from the national memory.