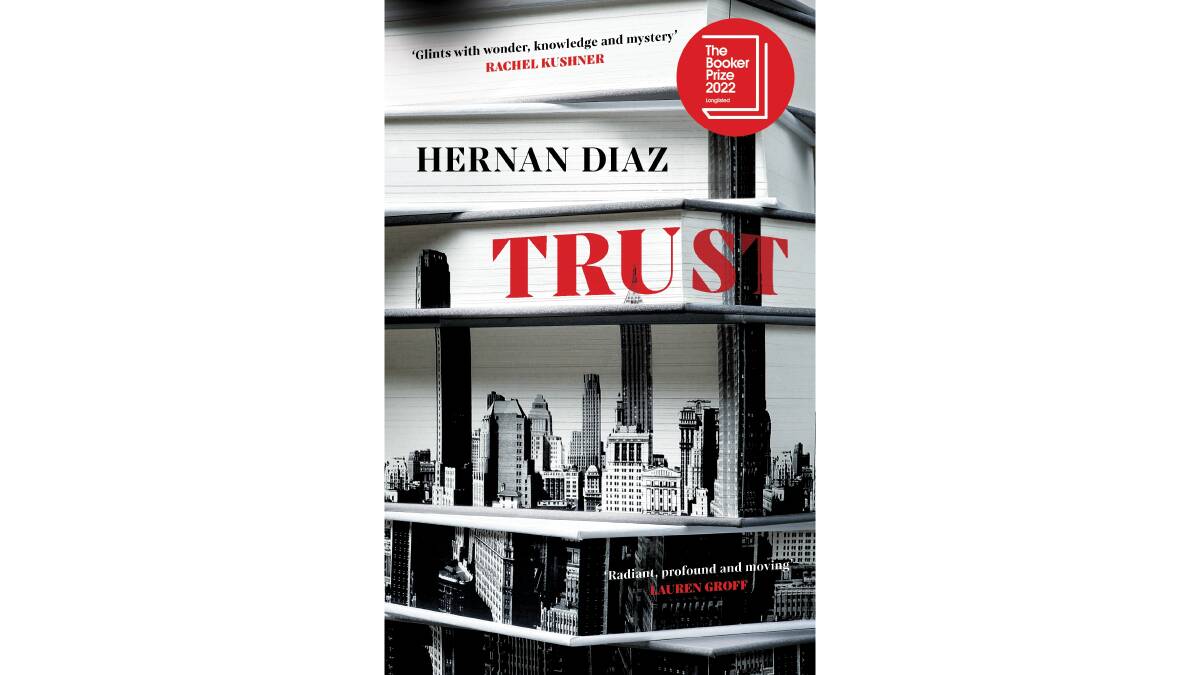

Trust by Hernan Diaz. Picador. 403pp. $32.99.

Cultural appropriation may take rather whimsical forms.

John le Carre reckoned that writing about his spymaster, George Smiley, became impossible after Alec Guinness had portrayed, captured and defined the character on television. Similarly, any writer tempted to venture back into the 1920s might feel that Scott Fitzgerald conclusively claimed that decade as his own with The Great Gatsby.

Nonetheless, Hernan Diaz is not easily deterred. Trust, long-listed for the Booker prize, offers not one but four versions of one story - sometimes competing, occasionally complementary - about the Jazz Decade. That literary technique is hardly new. William Faulkner revelled in a medley of narrative voices, and there are, after all, four Gospels. Diaz, though, has breathed new life and wit into an old trick.

Diaz first introduces his financier hero as a solitary; adjectives like aloof, diffident or private do not begin to cover the depth of his detachment from the world. This passive inheritor of wealth from tobacco sales had "no appetites to repress". This man without qualities, however, turns into an extremely deft student of stock market fluctuations and opportunities.

Such success entails embracing risks. Unfortunately, stock market risk-taking remains bloodless and soulless. Diaz is an artful, intelligent writer, but injecting drama into reading the ticker tape is a bit like drafting a novel about counting cards or checking the track times of race horses.

Diaz does gild the speculator's lily, suggesting that he discovered "a hunger at his core", then became "fascinated by the contortions of money". America's robber barons injected drama, combat and panache into their money-making. Here, by contrast, the business of business - let alone the busyness of business - seems to elude Diaz.

That is odd because otherwise Diaz is intently observant. Detail is dissected, appraised and tinkered with. The minute, grating gradations of status, wealth and insults are evaluated in a manner sometimes worthy of Edith Wharton.

After the first narrative voice, a purported biography, Diaz moves on to "a financier in a city ruled by financiers", a secretary with a stubbornly radical father and a woman fading away in a sanatorium. She is given the most intriguing line, contending that "God is the most uninteresting answer to the most interesting questions". The benighted secretary has to resolve some absurd blackmail allegedly involving the FBI.

The quartet of voices is uneven and disjointed, as unreliable narratives are meant to be. More critically, the central story is not vivid or engaging enough to sustain a reader's attention or do justice to Diaz's technique.