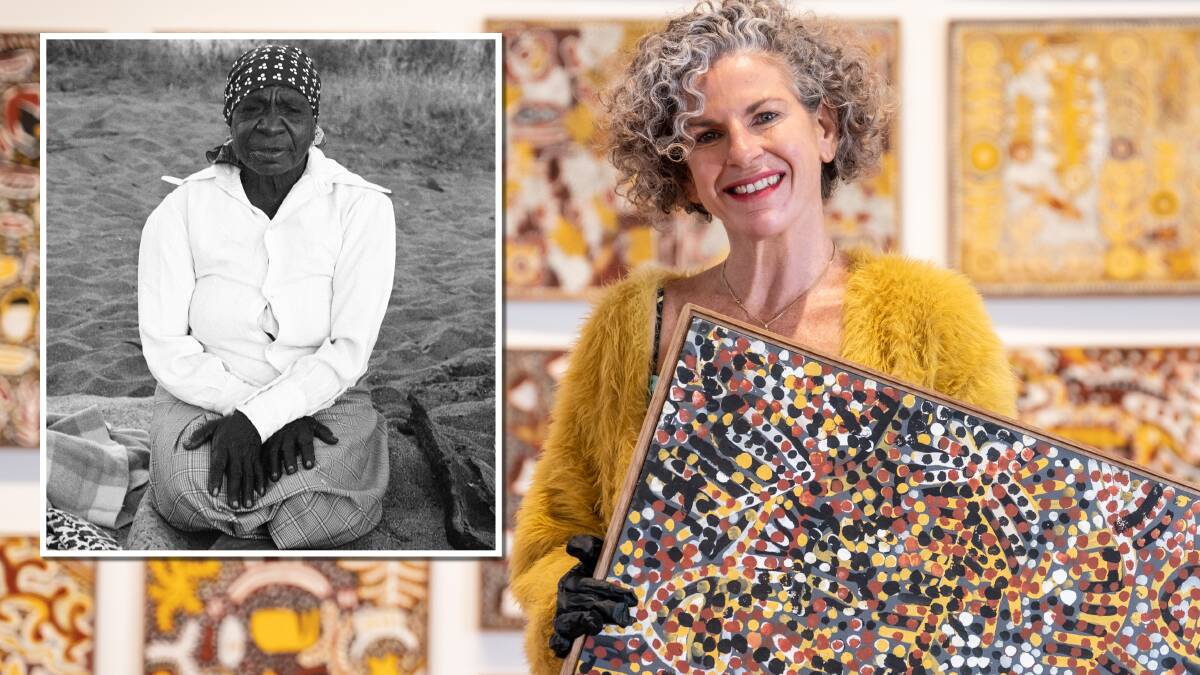

It was springtime last year in New York when Kelli Cole and Hetti Perkins found themselves at Sotheby's.

They were there to watch a selection of Australian Aboriginal artworks go under the hammer, and one work in particular had them excited.

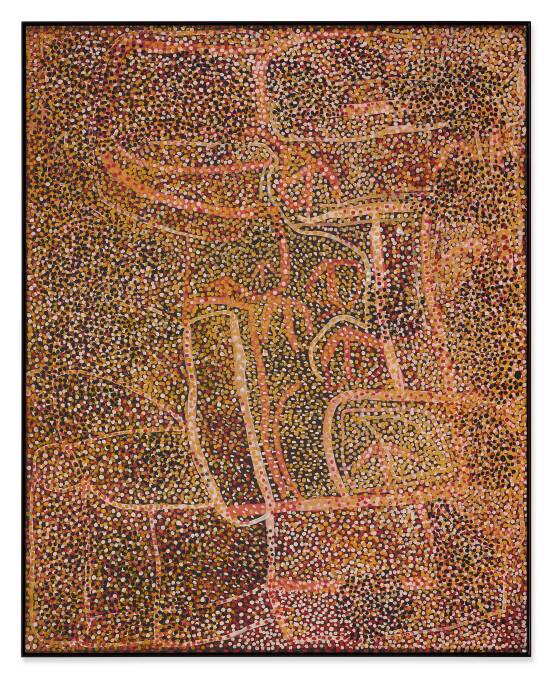

Old Man Emu With Babies was one of Emily Kam Kngwarray's earliest paintings, created in 1989 when she was around 75 years old and just starting out on a brilliant career that would run for the last eight years of her life.

The artist - a senior Anmatyerr woman and one of the most significant contemporary painters to emerge in the 20th century - is legendary for having begun painting late in life, and for her subsequent prodigious output.

Her works - she created some 3000 paintings over an eight-year period - are in private and public collections all over the world.

At this Sotheby's auction, there were three other Kngwarray works up for sale, but Old Man Emu With Babies was the one Cole and Perkins were watching.

The pair of Indigenous Australian curators were deep in the planning stage for a major retrospective of Kngwarray's work at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. And in New York, they were about to meet one of the private collectors who would, hopefully, agree to loan some of his stellar examples of her work for the show.

The collector was actor and comedian Steve Martin, and he was the winning bidder at Sotheby's that day, securing Old Man Emu for US$819,000 (around A$1.14 million).

"When you see this work, when all of these gallery lights are off, and it's spotlit, it's just luminous," Cole told me later.

"You've got the beautiful little emu marks of the father, and the other thing is, having all this consultation with community, I didn't know this, but the male fathers look after the chicks, not the mothers, which is really extraordinary."

Old Man Emu - and all of Kngwarray's works - are extraordinary, especially when displayed chronologically.

And the thing is, even in the tony surrounds of the famous auction house, and even later, at Martin's gargantuan Central Park apartment on whose walls his Kngwarrays are proudly on display, the epic works just sing of the desert.

Much has been written about Kngwarray's work, about who and what influenced her, and where her work fits into the canon of Australian, Indigenous and 20th century art. But the fact remains that her life and experience was centred on a piece of the world that was at once small, in the scheme of things, and vast, in terms of the inspiration it gave her and her community.

The upcoming exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia puts aside much of this writing and scholarship, and starts again from the ground up. Cole, a Warumunga and Luritja woman and Perkins, an Arrernte and Kalkadoon woman, have returned to her community at Utopia and recast her story as one of community and connection.

Connecting to country

It's October, about a year and half after the New York experience, and Cole is back at Utopia, on Alhaker Country, about three hours north-west of Alice Springs, where Kngwarray lived and worked.

I'm there too, one of a group of journalists there to learn more about the landscape of Kngwarray's life and work.

We're only in Utopia for one day, and there will never be enough time to completely absorb a landscape, or even adjust to one's surroundings. The dichotomy - between Canberra and Utopia, or even Alice Springs and Utopia - is just too stark to take it all in.

Cole lives in Canberra but grew up in Alice Springs, and as we drive out into the desert, she relaxes and speaks of the land's healing effects on her. It's blazingly hot under the blue, cloudless sky, and the low scrub extends around us, broad and expansive, dotted with trees and red rock formations.

On the drive there, in an air-conditioned bus, I had already clocked the startling green flash of the flocks of native budgerigars that flicker like mirages across the scrub. Their presence, I'm told, means there's water nearby. And we'd seen mysterious plumes of smoke just off the Sandover Highway that, every now again, materalised as smouldering grasses, sometimes licked by actual flames, caused by birds that deliberately drop burning twigs onto thickets of scrub to smoke out some game to eat.

And then, there's the actual desert, and the landscape that is so familiar to the people around us, and so heart-stopping to anyone else. I feel every kind of cliche about insignificance, about stepping into an ancient landscape, into time standing still, into timelessness.

We're spending the day with Kngwarray's descendants and members of the Kngwarray Long, Kngwarray Pruvis and Petyarr Kunoth - women who all have living memories of the artist, and many of whom are artists themselves. They call her, fondly, Old Lady, and remember her with smiles, and silences, and racing words and, sometimes, melancholy.

Over the course of an hour or two, they bring their memories to the surface, of a quiet, laughing woman who told stories, practised bush medicine on them, and painted all the livelong day, from sunrise to sunset. With big sections of canvas spread out before on the ground, she sat cross-legged in the shade and applied paint with a long brush.

The now-grown women, many with children and grandchildren of their own, remember bringing her food, filling up canisters of water for her brushes, and listening to her yarns.

She didn't talk about her work - the work itself did the talking and, as the women today tell it, she kept "her secrets for herself". There's a confused kind of silence when we ask whether she ever taught anyone to paint. This isn't how it works, we're told. The painting is innate, it's just what she, and others around her, did.

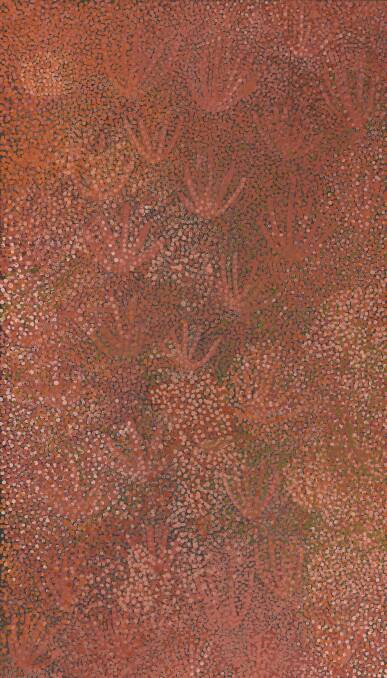

Later, we drive out to see more of Alhaker country, the place that fills Kngwarray's canvases, that represent emus, seeds, and yams, as well as awely, or body paint, the practice of painting the chest, neck and shoulders.

In fact, as an Anmatyerr elder, she had been doing ceremonial painting on the body for decades, and in 1977 became a founding member of the Utopia Women's Batik Group. Batik was arduous work, involving boiling the fabrics and layer upon layer on wax.

But the common narrative has it that Kngwarray didn't paint a brushstroke until 1988, when Rodney Gooch, the manager of the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association, distributed 100 canvases and paints to the Utopia women, Kngwarray among them, a new medium where before they had focused on batiks.

Over a four-week period in the summer, 80 painters completed 81 works, and a new era was born. The Holmes à Court Collection acquired all 81 paintings, and all are on display at the entrance to the new exhibition at the NGA. Kngwarray's stands out, her first canvas showing a different sensibility to the others. And from then, she seemingly didn't stop until her death eight years later.

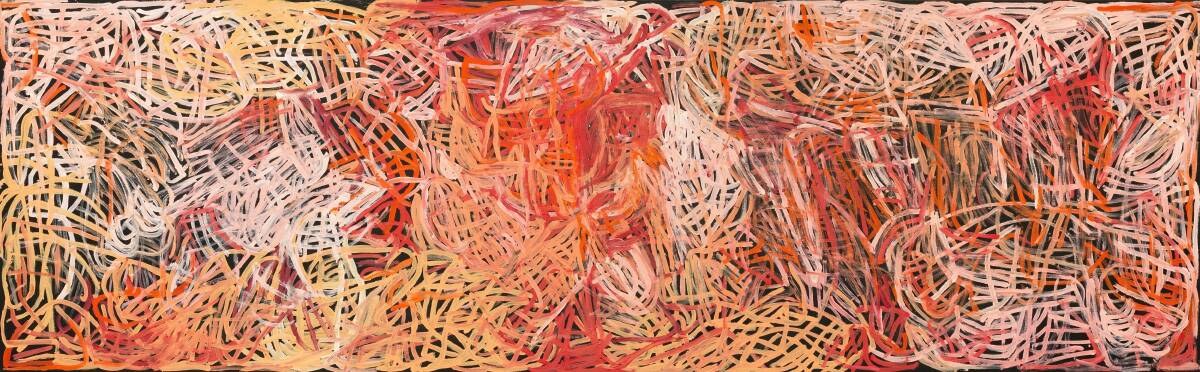

Her work was in direct response to the shape and contours of the landscape, the seasons, the soaking and flooding, and the patterns of seeds and plants.

As soon as you know this, her paintings, particularly up close and en masse, spring to life.

To the naked eye, for example, pencil yams start as a lush green tangle spreading across red soil.

Called anwerlarr in the language of the Anmatyerr people of the central desert, the yams have long, thin roots and seed pods called kam.

Kngwarray painted all three layers and all three stages, as integral parts of her life, and the world around her. And there they are, these huge canvases covered in tangled lines that fill every corner.

Her spirit all around

Kngwarray is buried in a very conventional grave of black granite, in a remote spot surrounded by the country she painted, and was herself made of.

On the day that we visit, her family members drive us to see, and we're told this is a rare occurrence. "Hello, lady!" the ladies sing out, and together they pat and stroke the hot granite, then stand together to be photographed around the resting place of their beloved Old Lady.

Seeing her here feels almost incongruous, and it's not just because of the remoteness of the site, far from any traditional graveyard setting. It's that her spirit is all around us, throughout her country and all through her works. The women still speak of her in the present tense.

She barely needs such a monument, when her presence is felt so strongly everywhere you look.

It's getting dark by the time we head back to Alice Springs. The budgies are still flickering around the verges, and the grasses are still smouldering from the fire birds. But even as the darkness deepens, the country around us seems in sharper focus than ever.

And now she's here on the walls of the NGA, alive in every marking.

- Emily Kam Kngwarray opens at the National Gallery of Australia on December 2 and runs to April 28. Tickets and info at nga.gov.au.

- Sally Pryor travelled to the Northern Territory courtesy of the National Gallery of Australia.