Why isn't there an uproar about this? A third of our kids are not reading adequately, and the trend is worsening.

People complain endlessly about shortcomings in health services, especially as they get older. It's a pity they don't worry nearly as much about educating the next generation.

The Grattan Institute, a think tank, has come up with a plan to improve kids' reading performance, getting more of them into the category labeled "proficient", meaning "good enough".

A strong theme in the plan is stamping out what remains of the discredited teaching method called "whole language". That hippy-trippy bunkum took over in Australia in the 1980s, pushed by supposed experts and teaching unions. It impaired the reading skills of a generation of Australians.

Consider the numbers. The global Program for International Student Assessment finds that our year-10 students in 2018 were eight months behind the reading level measured in 2000. Since 2018, there's been no progress.

Australia's own National Assessment Program for Literacy and Numeracy shows improvements since 2012 for kids in year 3 and 5, but Grattan's analysis finds that their gains disappear by years 7 and 9.

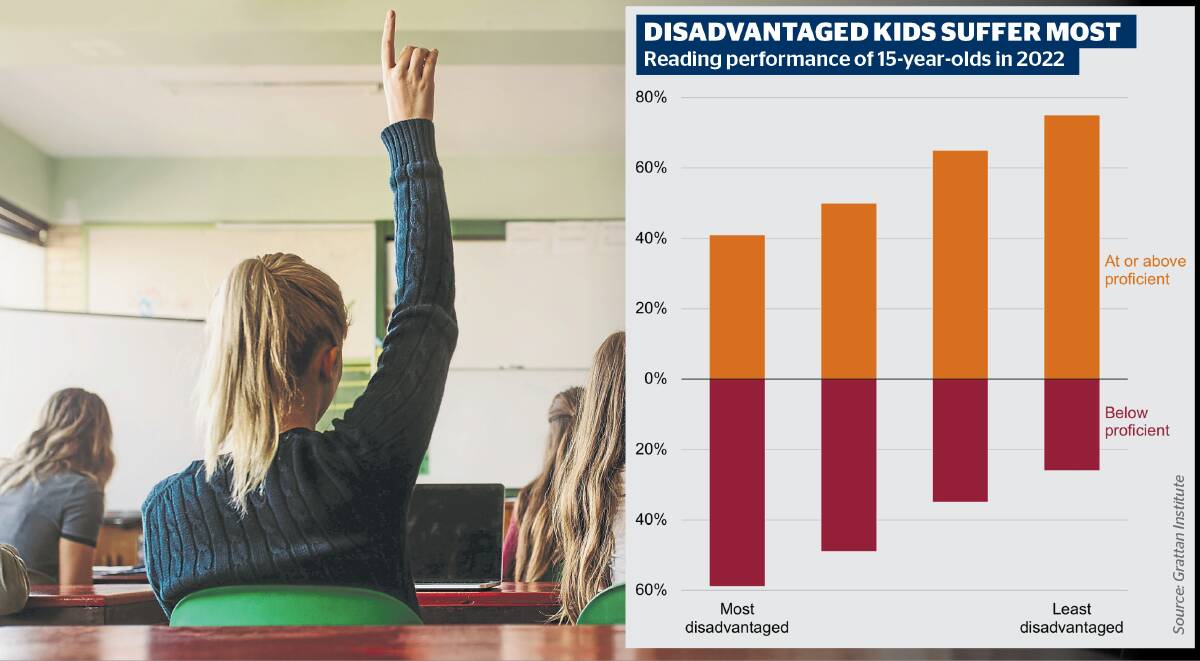

Only 68 per cent of year-10 students were proficient in reading last year - so about a third weren't. And it gets worse when we break down the numbers. For 15-year-olds from poor families, fully 60 per cent aren't satisfactory readers. For aboriginal kids of that age, it's 70 per cent.

Again, why isn't there an uproar about this? There would be in almost any Asian country. The Chinese Communist Party, for example, sees only one acceptable direction for national achievement in education: up. And it is determined to get it.

More to the point, almost all Chinese parents have the same attitude. With an intense interest in the education of their children, they'd be indignant if they understood that schools in their country, province or town were not delivering.

In 2022, Australian 15-year-olds were around a year behind Japanese and South Korean kids of the same age in reading, according to PISA. They were two years behind in maths. The gaps between Australia and Singapore, the world champion in primary and secondary education, are just astounding: two years in reading and about four years in maths.

And get this: Singaporean kids study not just English but also the language of their ancestors - Chinese, Hindi or Malay.

Australian results are in fact a little above PISA averages for reading, maths and science, but take no encouragement from that. The averages are dragged down by a majority of participant countries that are not on our side of the world, many of them poorly developed. Also, our position in the rankings has been dropping like a stone.

What came to be called the reading wars should be over. Study after study in Australia and abroad has shown the failure of whole-language learning. According to that sandal-wearing nonsense, children should discover how to read, more or less, instead of being taught step-by-step.

Education academics and government advisers who pushed it should be hung out to dry and kept well away from current policy. They've disgraced themselves and damaged the country.

The replacement is usually called phonics. That means teaching children how to associate letters with sounds, starting with regularly spelt words (such as "dog") before dealing with irregular ones ("walk"). But Grattan identifies phonics as only part of a larger recommended approach known as structured literacy - again, emphasising systematic instruction.

It's based on research and evidence, not politics or some huggy-huggy philosophy.

Over the past decade or so, Australian states and territories have been turning away from whole-language learning, but Grattan finds that more work needs to be done. Also, some governments have been slower than others in converting.

"The ACT and Victorian governments, as well as many Catholic archdiocese and independent schools, need to catch up to other systems that are taking the evidence about how to teach reading seriously," the think tank says.

It's notable that the ACT and Victoria are both dominated by the Labor party. Their ministers may want to consider whether they really want to associate Labor with slack education just to please recalcitrant left-wing defenders of whole-language learning.

Grattan proposes, first, to set a 10-year target of 83 per cent of Australian children becoming proficient readers. Then the long-term target should be 90 per cent.

Annual progress reports to parliaments are needed, and schools' performance must be monitored, Grattan says. We should give teachers more help in adopting the new approach, including setting the right curriculum and providing training and suitable class materials. Whole-language materials that are still in use should go in the bin.

Despite the improvement in teaching method, some kids will struggle. Grattan says more effort is needed to ensure they get special help, and they need to be identified before they begin to fail and become discouraged.

Still, we notice that Australian primary and secondary education has other problems. Our class discipline is abysmal, ranking 69th among 76 countries surveyed in 2018. Almost any teacher will tell you that kids' behaviour and attitudes have worsened over the years.

To some extent, that must flow from discipline at home, which brings up the issue of parental responsibility. And whether kids try hard also reflects their parents' emphasis on education. It's sad to say, but Australians just aren't as serious about it as Asians.

Our education problems are not just about the reading wars.

- Bradley Perrett was based in Beijing as a journalist from 2004 to 2020.