Bianca Welsh was living a happy life in suburban Australia. That world was turned upside down when she went digging for the truth about her family.

Adopted from South Korea as a baby, Ms Welsh is part of the shrinking group of inter-country adoptees.

Total adoptions in Australia have reached an all-time low of 201 in 2022-23. Only 28 of those were overseas adoptions.

That is down from a peak of 434 overseas adoptions in 2004-05 and some experts want inter-country adoption to cease altogether.

Bianca's best of both worlds

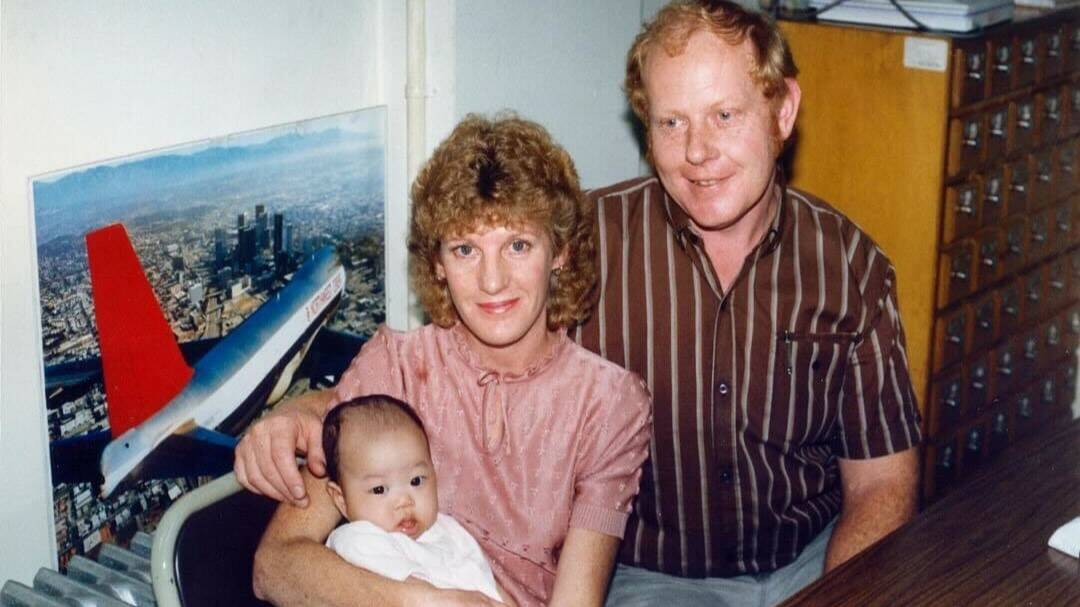

Born in Daegu in 1987, Ms Welsh was adopted at five months old by Launceston couple John and Susie Chellis who also had two biological children.

"Clearly I was of a very different appearance to the rest of my strawberry blonde, white, freckled, Caucasian family," the 37-year-old said.

She looks back on her childhood fondly and said being adopted allowed her "the best of both worlds".

Her parents took her to Korean lessons, visited South Korea, enrolled her in Korean martial art hapkido and celebrated Korean festivals.

However, her whole world was upended when she went searching for her biological mother.

Uncovering the real story

In 2011, Ms Welsh contacted Tasmania's department of human services after deciding she wanted to know her birth mother before having her own child.

The only identifying information she had were original typewritten forms stating the names and physical features of her parents.

Her form noted her parents had separated before her mother knew she was pregnant.

She heard back from the department three months later with a lot more than she had expected.

Not only were her parents still married but Ms Welsh was the youngest of three daughters.

"I had panic attacks, for the first time ever, I had emotions of feeling abandoned and unwanted," she said.

"In Korea at the time, if you had more than one girl, you were seen as a bad woman, because they already had two girls, the family was desperate for a boy."

Eventually, Ms Welsh found out that her mother had five abortions between her middle sister and herself - aborted because they were girls.

During her mother's pregnancy, doctors mistook Ms Welsh for a boy.

"I came out and she [paternal grandmother] said, 'you can't keep her, you have to get rid of her' and so my mum did, and put me up for adoption," Ms Welsh said.

She said 'you can't keep her, you have to get rid of her', and so my mum did.

- Bianca Welsh

"She left the hospital within a couple of days and told everyone, my father included, that I was a boy and that I died at birth."

"He didn't even know I existed."

Making contact, meeting family

After processing this news, Ms Welsh reached out to her biological mother. Her mother responded several months later in March 2012.

Exchanging photographs and sporadic correspondence for five years, Ms Welsh and her husband travelled to South Korea to meet the family for the first time in 2017.

"It was hugely overwhelming, I went looking for my mother and instead I got a whole family," she said.

"All my mum would do was hold my hand and say 'I'm sorry'."

All my mum would do was hold my hand and say 'I'm sorry'.

- Bianca Welsh

Today, they are still in contact and both families have visited each other's home towns.

Ms Welsh and her husband have two young children but are still considering adoption as a family option.

"If I could give the opportunity to another little girl like I was given, to go flourish and ... achieve what they want to achieve ... it is something we would still consider," Ms Welsh said.

Adoption on its way out

However, adoption may not be an option for the Welshes and other families.

South Korea is no longer accepting adoption applications from Australia in 2024 and other countries including the Philippines and Thailand have also ceased adoptions.

ACU's Institute of Child Protection Studies director Professor Daryl Higgins believes Australia should be aiming for zero overseas adoptions.

"I think that Australia is on the right track to realise this is not a preferred form of care for children, it's not a solution to their right to safety and wellbeing," Professor Higgins said.

He believes "there's no need for modern adoption" both locally and inter-country, with kinship and prevention initiative models preferred.

"The basic premise is that children have the right to be cared for by their parents, and the state has an obligation to support those parents and those children," he said.

"My biggest hope is that we have a groundswell of support for prevention initiatives that can stop children growing up in families where they are experiencing risk of harm."

13YARN 13 92 76

Aboriginal Counselling Services 0410 539 905