Delving through historical texts dating back as far as the 14th century, Regula's Ysewijn refreshingly original book Pride and Pudding documents the history of the British pudding, rediscovering long-forgotten flavours and food fashions along the way.

- Pride and Pudding: The history of British puddings, savoury and sweet, by Regula Ysewijn. Murdoch Books, $55.

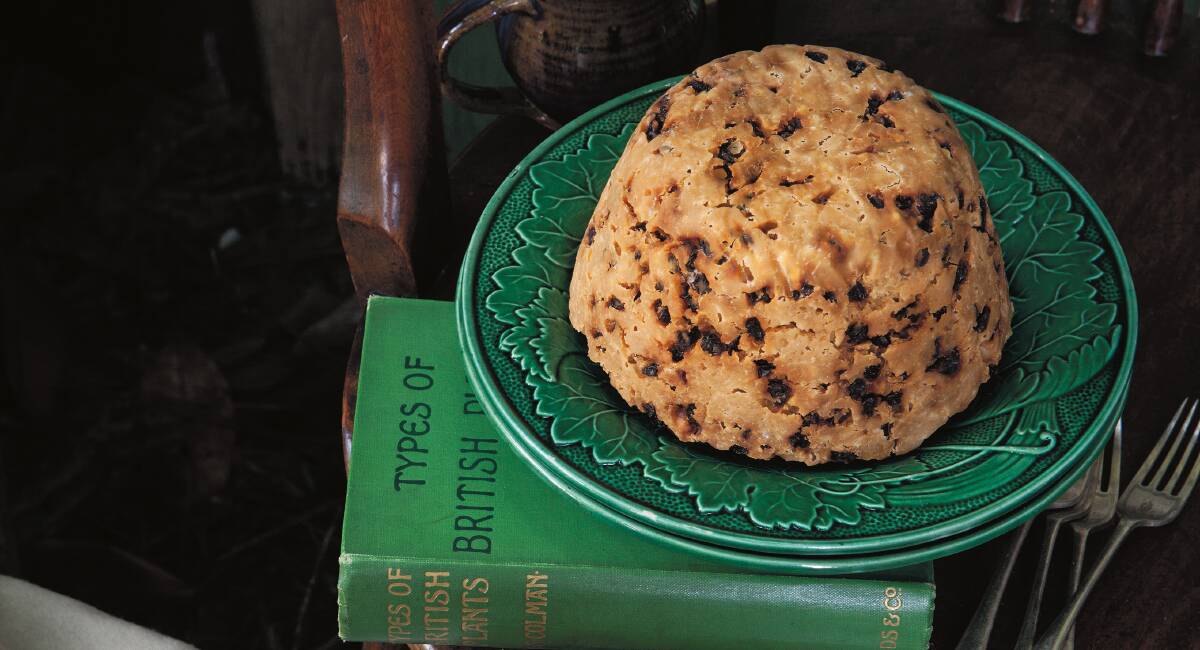

Spotted dick

Mentioning this pudding to people unfamiliar with British food always generates great amusement. Its etymology is the culprit, though an entirely innocent explanation can be provided. "Dick" is simply an old dialect pronunciation of "dough", just like "duff" in plum duff.

The first documented recipe for spotted dick appeared in A Shilling Cookery for The People in 1854.

339. Spotted Dick.- Put three-quarters of a pound of flour into a basin, half a pound of beef suet, half ditto of currants, two ounces of sugar, a little cinnamon, mix with two eggs and two gills of milk; boil in either mould or cloth for one hour and a half; serve with melted butter, and a little sugar over.

- - Alexis Soyer, A Shilling Cookery for the People, 1854

A few years earlier, in 1849, the same author had published another recipe for spotted dick in his book The Modern Housewife or, Ménagère. Then he called it a "Plum Bolster", or "Spotted Dick" - this recipe, however, was for a rolled suet pudding like a roly-poly. His recipe for roly-poly is printed just above the spotted dick in the book.

Nowadays the pudding is sold in tins, a reminder of how the English searched for a way to have their puddings without having to spend the time making them! Spotted dick was also a popular school-dinner pudding; many people who were young in the sixties and seventies will remember them well, all covered in custard. Well prepared, it is a treat and a pudding so iconic, especially because of its most peculiar name, that it could not be omitted from this book.

Ingredients

300g plain flour

130g shredded suet

50g raw sugar

a pinch of ground cinnamon

1 tsp baking powder

1 egg

200ml milk

150g currants, soaked in water, brandy or rum

Method

1. Preheat the oven to 160C. Prepare the pudding basin for steaming (see below).

2. Combine the flour, suet, sugar, cinnamon and baking powder together in a large bowl and mix well.

3. Add the egg and a little of the milk while constantly stirring the mixture. Soon it will be looking like very coarse breadcrumbs. Keep adding milk until you can bring the mixture together with your hands into a stiff dough. If it is too dry, you might need another splash of milk, although the dough should not be wet or sticky. Finally work in the currants.

4. Roll the dough into a ball and press into the prepared pudding basin. Steam the pudding in the oven, as described below, for four hours. Serve with custard sauce (see below).

Makes one pudding in a 17cm basin.

Steaming a pudding using a pudding basin

Preparing the basin

Generously grease the pudding basin with butter and cut a circle of baking paper the same size as the base of the pudding basin. Place the paper circle in the basin; it will stick perfectly to the butter. This will make it easier to get the pudding out of the basin.

Spoon the batter into the pudding basin, then cut another two circles of baking paper with a diameter about 8-10cm larger than the top of the basin. Make a narrow fold across the middle to leave room for the paper cover to expand slightly. I like to use two layers of paper. Tie securely around the top of the basin with kitchen string, then cover with foil and tie kitchen string to create a handle so it will be easier to lift the basin out of the pan after steaming.

Now get yourself a pan large enough to hold your pudding basin(s) or, if you are steaming little ones all in one go, a large baking dish. I prefer to use the oven for this as I do not like to have a pot of boiling hot water on the stovetop for two hours or more, depending on the recipe.

Preheat the oven to 160C or the temperature suggested in the recipe.

Stand the pudding basin on an inverted heatproof saucer, a jam-jar lid or trivet in the base of a deep ovenproof saucepan or pot.

Pour in boiling water to come halfway up the side of the basin. Cover the pan, either with its own lid or with foil, in order to trap the steam. Place in the preheated oven and leave for as long as your recipe states. This can be between 30 minutes and 7 hours depending on the size of your pudding.

When you are steaming little puddings, it is sufficient to place the puddings in a deep baking dish and fill the dish with boiling water once you have put them in the oven. Cover the dish with foil and steam for as long as your recipe states.

Unmoulding a pudding

Carefully remove the pudding from the pot while it is still in the oven. Have a tea towel at the ready to hold it safely and catch all the hot water that will drip from it. Leave the pudding to rest for a couple of minutes, so that it will cool off a bit and be easier to handle.

Have a plate ready. Remove the foil and string, then open the paper lid and turn the pudding out by carefully loosening it around the edges with a blunt knife.

READ MORE

Custard sauce

Gloriously flavoursome full-fat milk and cream and deep orange coloured egg yolks will give the flavour you need to make this a truly enjoyable sauce. Mace is excellent as a flavouring, a bay leaf added to it gives a more spiced flavour. When using cinnamon, the flavour is quite similar to using vanilla, I find, but vanilla - now commonly used - was never traditional.

Ingredients

10 egg yolks

500ml milk

500ml thick cream

50g raw sugar

1 mace blade or cinnamon stick

1 bay leaf (optional)

Method

1. Whisk the egg yolks in a large bowl. Bring the milk, cream, sugar, spice and bay leaf, if using, to a simmer in a saucepan. Strain the hot milk mixture and discard the flavourings. Pour a little of the hot mixture into the egg yolks and whisk thoroughly. Now continue to add the hot milk mixture in batches until fully incorporated and you get a smooth sauce.

2. Pour the mixture back into the saucepan and cook over low heat, stirring constantly with a spatula until just thickened, making sure the eggs don't scramble.

3. When just thickened, remove from the heat and pour into a cold sauceboat for serving. If you don't want the custard to develop a skin, cover the sauceboat with plastic wrap.

Makes about 2 litres.

Toad-in-the-hole

Hannah Glasse, who came up with the term "Yorkshire pudding" in 1747, also had a recipe in her book The Art of Cookery for "Pigeons in a Hole". It was basically a toad-in-the-hole using whole pigeons rather than sausages.

Fifty years later the novelist Fanny Burney mentions the trend for "putting a noble sirloin of beef into a poor, paltry batter-pudding!" (Diary and Letters of Madame D'Arblay, December 1797). Sausages were being used in this manner as well; in the mid-18th century the diarist Thomas Turner mentions that he "dined on a sausage batter pudding" (February 9, 1765).

Richard Briggs, in The English Art of Cookery (1788), is the first instance I can find that actually names the dish Toad-in-the-hole, although his version uses beef.

Alexis Soyer gives not one but eleven versions of a toad-in-the-hole in A Shilling Cookery for the People (1854), his book aimed at the working classes. The first uses "trimmings of either beef, mutton, veal, or lamb, not too fat"; then there is a plain version with potatoes, and one with peas. Further, he suggests to use calves' brains; larks or sparrows; ox cheek or sheep's head; a rabbit; the remains of a previously cooked hare; a blade-bone of pork; and finally the remains of salt pork.

The next mention I wish to share with you comes from the Italian Pelegrino Artusi. He mentions a recipe for toad-in-the-hole in La Scienza in Cucina e l'Arte di Mangiare Bene (1891). The recipe is called "twice-cooked meat English style" (lesso rifatto all'inglese) and in his description he mentions that "toad-in-the-hole" is the name of this twice-cooked meat. He also goes on to explain that it is a delicious dish and it would be an insult to call it a toad. Artusi had a great sense of humour and that is something you can see in his introductions to his recipes.

However, the toad-in-the-hole he mentions is not for a sausage cooked in batter, but uses meat for boiling, sliced and browned on both sides. What becomes clear is that the toad-in-the-hole is a popular dish to use up leftovers at this period in time. Mary Jewry gives three recipes for toad-in-the-hole in her book, Warne's Every Day Cookery: one for a batter pudding with a veal-stuffed chicken, one with rump steak and one to use up cold roast mutton.

During the war years, people were instructed to cook toad-in-the-hole using Spam rather than the (by then) more commonly used sausage. Today the dish has become so connected with British food culture it is no wonder references can be found as early as the mid-1700s.

Toad-in-the-hole is now a favourite dish of small and tall: every child loves a banger, and every grown-up likes to be transported back to his or her childhood. It now features on the menus of laid-back pubs and restaurants that prepare it with posh locally sourced bangers. And a festive Bonfire Night, too, wouldn't be the same without it.

Ingredients

3 or 4 good-quality pork sausages

sunflower oil or clarified butter, for frying

a few sprigs of rosemary (optional)

1 quantity Yorkshire pudding batter (see below)

Method

1. Preheat the oven to 250C.

2. Fry the sausages in sunflower oil or clarified butter in a frying pan until nearly cooked through.

3. Pour 1cm of sunflower oil, clarified butter, lard or tallow into a baking tray or cake tin and set it in the middle of the hot oven. Place a larger tray underneath in case the oil drips; you don't want extra cleaning and a smoky kitchen afterwards.

4. When the oil is hot (you will see it spitting), arrange the sausages in the tray along with any oil or butter remaining in the frying pan. Carefully but swiftly pour the batter into the hot oil, stick in the rosemary sprigs, if using, and close the oven door. Bake for 20-25 minutes without opening the oven until the pudding is puffed up and nicely coloured.

5. Serve with mustard, braised red cabbage, jacket potatoes or mashed potato and caramelised onions, if you like.

Serves 3-4.

Yorkshire pudding

Ingredients

110g plain flour

a pinch of salt

280ml milk

3 eggs

sunflower oil, clarified butter, lard or tallow, for frying

Method

1. Proceed by creating the batter as you would for a pancake batter, adding the flour and pinch of salt to the milk and eggs, making sure there are no lumps. I find that the pudding improves if you leave the batter to rest for 30 minutes or so before cooking.

2. Preheat the oven to 250C.

3. Pour 1cm of sunflower oil, clarified butter, lard or tallow into a baking dish or cake tin and set it in the middle of the hot oven. Place a larger tray underneath in case the oil drips; you don't want extra cleaning and a smoky kitchen afterwards.

4. When the oil is hot (you will see it spitting), carefully but swiftly pour the batter into the hot oil and close the oven door. Bake for 20-25 minutes without opening the oven until the pudding is puffed up and nicely coloured.

Serves 4-6 people.

Queen of puddings

A pudding with such a regal name must be of royal origin. Except it isn't. Some claim it was invented in honour of Queen Victoria, but it wasn't. Puddings using milk-soaked bread, custard and jam were plenty in historical cookery books. The first time one appears under the name queen of puddings is in Massey and Son's Comprehensive Pudding Book, where it is named "A queen's pudding". The pudding is made of a layer of custard thickened with breadcrumbs, on which a layer of jam is spread followed by a layer of pretty meringue swirls.

Add one pound of bread crumbs to one quart of milk, a quarter of a pound of sugar, the zest of a lemon, two ounces of butter, and four eggs; bake in a buttered pie dish; when done, spread the top of the pudding with apricot jam, and mask with meringue; set in the hot closet, and serve cold with whipt cream in a boat.

- Massey and Son's Comprehensive Pudding Book, 1865

The modern recipe usually uses raspberry jam (it appears the Brits have a love for raspberry jam). Alan Davidson, author of the formidable Oxford Companion to Food (3rd edition, 2006) notes that this pudding, in its modern form, is one of the best British puddings.

Ingredients

butter, for greasing

4 egg yolks

600ml milk

20g raw sugar

zest of 1 lemon

25g unsalted butter

80g fresh breadcrumbs

2 tbsp raspberry jam

Meringue:

4 egg whites

225g caster sugar

Method

1. Preheat the oven to 180C. Generously grease the ovenproof dish or individual basins with butter.

2. Whisk the egg yolks in a large bowl. Bring the milk, sugar and lemon zest to a simmer in a saucepan. Now add the butter and melt it, making sure the mixture doesn't boil.

3. Pour a little of the hot milk mixture into the egg yolks and whisk thoroughly. Continue to add the hot milk in batches, stirring until fully incorporated and you get a smooth custard sauce.

4. Make a layer of breadcrumbs in the buttered dish, or divide them between the individual moulds, then pour the custard sauce over and let it rest for 15 minutes.

5. Prepare a deep baking dish with boiling water and place the dish or small pots in it. Carefully place the baking dish with the pudding(s) into the oven and bake for 35 minutes.

6. Towards the end of the baking time, make the meringue topping. Whisk the egg whites using an electric mixer until you get soft peaks when removing the whisk. Add the sugar a tablespoon at a time, still whisking, until the meringue is stiff and glossy.

7. Remove the pudding from the oven and spread the raspberry jam over the custard layer making sure you don't break the custard layer. Now either scoop the meringue onto the hot pudding, or scoop into a piping (icing) bag and make fancy swirls or peaks.

8. Return the pudding to the oven until the meringue is slightly coloured, which will take 15-20 minutes. Serve warm or cold.

Makes 6 individual puddings, or use one 18 cm ovenproof dish.

Apple charlotte

The apple charlotte is a relative of the summer pudding. Both are puddings made in a mould lined with slices of bread, and both hold some kind of fruit. It is said that the apple charlotte is named after Queen Charlotte, the wife of King George III, who might have been the patron of the apple growers.

Some have claimed this pudding was invented by the French chef Carême in 1802, and that he published a recipe for "charlotte a la parisienne" and later changed it to "charlotte russe" when he worked for Tsar Alexander of Russia; however, in that same year a recipe for charlotte of apples was published by John Mollard (The Art of Cookery Made Easy and Refined, 1802). Moreover, Carême only published his first book in 1815, not 1802, and as far as I know the pudding does not appear in it. In 1802 Carême was an 18-year-old apprentice, working for a pastry chef who encouraged him to learn to read and write. Hardly a time at which he would write a book.

Although the earliest recipe in print I could find is John Mollard's, it is very possible this pudding did appear earlier in manuscript recipe books. What we do know is that it is more likely that the apple charlotte is an English invention after all.

Charlotte of apples.

Stew some apples with a bit of fresh butter, a little syrup of quinces, half a pound of apricot jam, and half a gill of brandy; rub all through a hair-sieve, add a few dried cherries, and put into a mould lined with bread cut in diamonds of four inches square and half an inch thick, and previously dipped in oiled butter. Cover with slices of bread, likewise dipped in butter, bake of a light colour, and sift sugar over.

- - John Mollard, The Art of Cookery Made Easy and Refined, 1802

John Mollard instructs the cook to make a pulp of apples, stewed with brandy, a little quince syrup, apricot jam and dried cherries. Mary Eaton, in The Cook and Housekeeper's Dictionary (1822), uses thinly sliced apples, layered with butter and a little sugar until the mould is full. Mollard tells us to dip the bread in butter, while Eaton omits that step

Ingredients

3 cooking apples, such as granny smith or bramley, about 500g, peeled and cored

5 tbsp apricot jam

60ml brandy or dark rum

1 loaf of stale plain white bread, about 550g

50g butter, melted sugar, for sprinkling

Method

1. Preheat the oven to 190C. Generously grease the mould or loaf tin with butter and place a disc or strip of baking paper in the bottom.

2. Chop up the apples and put them in a saucepan with the apricot jam and brandy. Cook until soft and pulpy. You might need a splash of water to prevent the apples from burning. Allow to cool in the pan.

3. Cut thick slices of bread in 5cm wide rectangles the same height as the side of the mould and use a pastry brush to generously coat them with the melted butter.

4. Place the bread in the mould, overlapping the edges a little so there are no gaps. Finally put a disc or strip of bread onto the bottom of the mould, making sure there are no gaps.

5. Scoop the apple mixture into the bread-lined mould, then close the top with a final few slices of buttered bread and sprinkle some sugar on top.

6. Bake in the middle of the oven for 30-40 minutes until golden brown, as you prefer your toast. When ready to serve, turn the mould onto a plate and allow to stand for 5 minutes before attempting to remove the mould.

7. Serve with clotted cream, brown bread ice cream, vanilla ice cream, or custard sauce for the custard lovers.

Makes enough for one charlotte mould or 16 x 10 x 7.5cm loaf tin.

We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on The Canberra Times website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. See our moderation policy here.

Our journalists work hard to provide local, up-to-date news to the community. This is how you can continue to access our trusted content:

- Bookmark canberratimes.com.au

- Download our app

- Make sure you are signed up for our breaking and regular headlines newsletters

- Follow us on Twitter

- Follow us on Instagram